A Little Optimism Goes A to Z: Stacey Allen and Brynne Henry Release Their Second Dance Book for Children

Once upon a time, Stacey Allen, the artistic director for Nia’s Daughters Movement Collective, was a public school dance educator. While teaching elementary aged dance students, she noticed a lack of materials that spoke to African American dance history. In Allen’s own life and practice, the choreography and scholarship of Katherine Dunham were important to her and so of course she would want to reference Dunham in her teaching. Most materials available on Dunham, however, were made for much older audiences. She found some materials on other figures such as Alvin Ailey, but she decided Katherine Dunham presented a substantial hole that needed to be filled.

So, while still teaching, in 2016, Stacey Allen wrote the first draft of her first book, A Little Optimism Goes a Long Way, on a sheet of notebook paper.

The lessons about Dunham are indirect. “A Little Optimism Goes a Long Way follows the story of a young girl named Nia who is starting her dance journey,” Allen says. “This young girl has to get over her stage fright so there’s the opportunity to teach about confidence and social-emotional learning, hence the title.” While that’s the universal, surface story being told, the secondary, dance history story unfolds as Katherine Dunham becomes a hero to the young dancer.

A tertiary level of African diasporic art education gets layered into the pictures in the book. Posters of other dancers of the African diaspora are on the walls of the dance studio where Nia takes class and her family has their home decorated with African masks, art prints, or posters with quotes from African American writers. With such dense layering of information casually sprinkled throughout, it’s little wonder that this independently published picture book still managed to become a local bestseller at Kindred Stories bookstore in Houston’s Third Word.

Furthermore, A Little Optimism Goes a Long Way just received the National Association of Multicultural Education’s Multicultural Children’s Publication Award in a ceremony that took place on November 16 in Anaheim, California. This made for a big finish for the book’s first year of publication.

But that was last year. This is this year.

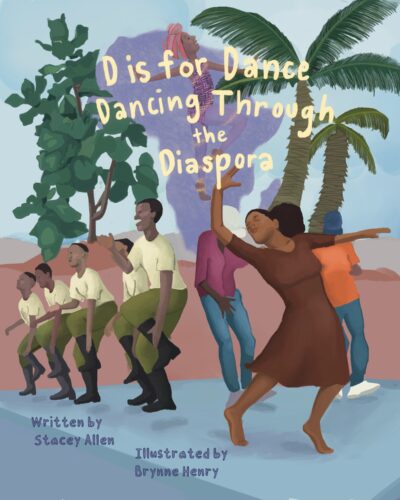

This holiday season, Stacey Allen, along with her collaborator, artist Brynne Henry, will be releasing their second book, D is for Dance, Dancing through the African Diaspora. “Essentially, the goal is to go A through Z of different dance styles of the African diaspora, again, as a teaching resource of different dance styles,” Allen explains. “When I say African diaspora, I’m talking about everything from the continent to the Caribbean to the United States to parts of Latin America—all the places that people of African descent were forcibly displaced to or willingly migrated to.”

This is a good place for a little flashback on the development of this collaboration. As Allen developed A Little Optimism, it was Allen’s mother who saw Henry’s drawings and drew Allen’s attention to Henry’s Instagram. This was in 2020, while Henry, who is from Houston, was studying art history and education at the University of North Texas in Denton. The interest and focus on African diaspora history and art was something they found they shared, as well as their initial career starts in K-12 education. “I got a fellowship where I studied African American art history at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York. In doing that I learned a lot about black history in the arts, like black theater. When I met Stacey and she wanted me to illustrate black dance, I felt like it was a good opportunity to learn another facet of Black art,” Henry says. “It feels like a continuation of my studies of African diaspora history when I was in college.” For example, Henry came into the first book with little knowledge of dance history and it’s figures so didn’t know who Katherine Dunham was. “And then when I had to draw the posters that are on the wall in the dance studio, I had to learn who Alvin Ailey was and who Bojangles was.”

Henry’s dance history lessons didn’t stop with that first book. “When I was growing up, we would dance at family reunions, we would dance in school, and it was always a nice way to build community,” Henry says, “But I didn’t know it extended into history. Through reading this [second] book, it was interesting finding how the dances we did when I was a teenager connected back to decades of black dance and our heritage.”

“Dance brings people together in so many avenues so I was intentional about not making A to Z only about concert dance,” Allen says. “I love me some concert dance, I’ll always be in the audience when Ailey comes, but I think it’s really important to incorporate not only concert dance but also social dances. So S is for Second Line. Z is for Zydeco. Those are ways to pull in people who may not have a dance background, but—they have a dance background.”

Allen is open about being creative in how she used the alphabet to slip in as many dancers and dance styles as she could. For example, O is for Ostrich Dance gets a page about Sierra Leone choreographer Asadata Dafora and his famous dance entitled Awassa Astrige, which borrowed movements and mannerisms from ostriches.

“Probably the most creative we did was Q,” Allen says. “Brazil is home to a lots of different African diaspora movement forms. Of course, you have Samba and Capoeira. Quilombos are Maroon societies in northeastern Brazil in Bahia.” It was in these remote communities of formerly enslaved peoples that movement forms most kept their direct lineage to Africa. “This was an opportunity to share that world history.”

The collaboration between these two women often feels more than serendipitous to them. Even after they started work on A Little Optimism they kept learning about shared interests and parallel practices. They both have spent time exploring Freedmen’s towns. Both have worked within the Black traditions of quilting and collage. They are intentional about layering all this knowledge and experience into their work, including these books.

“I hope that when educators, parents, students—when they read the book,” Allen says, “I hope that this passion to pass on our traditions is evident, because all these things are intentional.”

Recent Comments