Choreographing Memory: Mark Aguilar Explores His Sister’s Experiences

Choreographing Memory: Mark Aguilar Explores His Sister’s Experiences

“Metamorfosis”

Choreographer – Mark Aguilar

Performer – Aniya Wingate

Mark Aguilar’s six-and-a-half minute dance, “Metamorfosis,” starts with a montage of home video, at least one of which is date-stamped in 2009. The focus is children. Driving kiddie racecars and bumper cars. Swinging in a backyard. A family activity taking place around a table. The images appear faded, almost black and white, emphasizing that these are not recent images. We are in the past, in the realm of memory.

While the video is projected on the back wall of the stage, a solo dancer, in darkness before the screen, watches, turns away, turns back, collapses. It’s clear the dancer has a relationship to the videos. It’s clearer the emotions provoked are complicated. The music for this section is a moody, sparse song. A repeated line is “quitame la piel de ayer.” With the help of Google, I learned this translates to “take off my skin of yesterday.”

As the video ends, more light is shown on the dancer, letting us see her white dress is a traditional Mexican dress with red and green embroidery around the yoke and hem. Both sides are slit, up to the hips, presumably for ease of movement for the dancer, although it is possible there is more symbolism to this than I perceived. She wears a red ribbon in her hair. The music shifts to a violin instrumental. The dancer plants her feet wide, cupped hands trying to lift something up, but the weight is too much. She collapses. She tries again, again she collapses. What follows is lyrical choreography of someone trying to handle a burden with grace. She presses upward, momentarily bearing the burden before falling to the floor. She rises again, reaching as if for help, but again falls. This section evoked, for me, the feeling of someone doing their best to rise to the occasion, but not succeeding or at least not maintaining success for long.

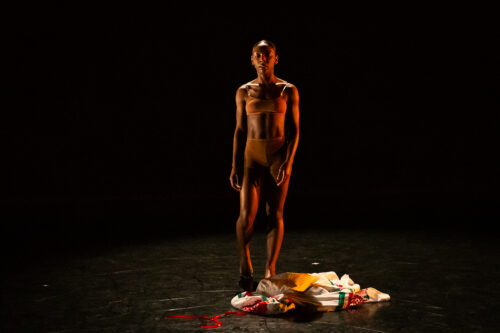

The transition to the last section starts with flashing red lights on the back screen. An emotional, dramatic ballad plays. “El Triste,” “The Sad One.” Throughout this section, the dancer’s movements become stronger but repeating the themes of the previous section. She dances assertively, as though declaring her own identity, her own wants, still falling but getting up with more and more strength and determination. At the crescendo of the ballad, the dancer stumbles to the floor in exhaustion. As she kneels on the floor, she reaches to her hair, removes the red ribbon, drops it. She slowly stands during the final long note of the song and backs away from the audience, arms extended downward, suggesting both a declaration and a surrender. The wall behind her flashes red again. In the silence that follows the song, she peels the dress off, starting with her shoulders, down her body, over her hips, and finally steps back, out of it. She wears a sports bra and Lycra sport shorts that are a very close match to her own skin color, giving her the appearance of being nude. She pauses to face the audience, one last declarative posture, before turning and exiting the stage.

It should be noted that dancer Aniya Wingate plays the role with range and precision. She attacked the choreography with an openness to both the strength and the vulnerability that Aguilar’s movement asked from her.

That’s what I saw. Some of it was informed by a program note that explained that what inspired Aguilar’s choreography was his older sister. They are children of immigrants and he grew up watching his sister, from a very early age, having to play translator for their parents, helping to read documents that she was too young to have a context for translating.

Dance, if it has a narrative, is an abstraction of a story. Aguilar isn’t creating a literal history of his family. What interests me is the distance between the family history and this abstracted solo dance. The central figure is not telling her own story. Aguilar is telling us the story through a dancer who, presumably, was not present to the lived reality. Is he a reliable narrator? Is the portrayal, full of resilience and strength, idealized by an admiring little brother?

It is a form of translation. of an observed and even shared life turned into gesture and symbol. Aguilar saw some sort of transformation as his sister came into adulthood. I see the “piel” of the first song in the dress that is shed.

Maybe little of this matters. Someone who saw the dance without reading the program note might have easily seen other things, gone away with other questions. This may all be the musings of a dance writer with too much time to muse.

But Aguilar’s story ends when we see the dancer take off the “skin of yesterday.” The choice of a Mexican embroidered dress suggests she is peeling off some part of that heritage. Like a good literary story, we aren’t given all the answers but left with questions of “what now, what next?”

Personally, I’m left wondering if there is a follow-up for this dance. I wonder if it is the first part of a longer work. I wonder what skin the dancer will wear after her “Metamorfosis.”

Recent Comments