Knowing Through Dance

A Look at the Artists in Residence Performing in Barnstorm Dance Fest’s Tenth Anniversary Program

Adele Nickel, Ashley Clos, and Paty Lorena Solórzano. What this, the tenth cohort of Dance Source Houston’s Artist in Residence (AIR) program, does brilliantly is to show that dance can grapple with topics as universal and esoteric, as intricate and voluminous, as concrete and ethereal as any other art form. That fact shouldn’t need defending at this point, but on the strength of these artists, we can prove it to Houston so our city can help lead the zeitgeist: movement is knowledge, is culture, is theory, is art.

The shining evidence will be on view during Barnstorm Dance Fest, April 28-May 3 at MATCH, 3400 Main St, Houston TX 77002. The format of Barnstorm is a three-program offering – programs A, B, and C – where each program is presented twice during the festival, once with a post-performance, facilitated artist talk. Ashley Clos’ piece is in program A, Paty Lorena Solórzano’s in program B, and Adele Nickel’s in program C. As usual, the programs showcase dance talent from across the Houston dance community, as well as artists it attracts from elsewhere. As members of the prestigious and competitive AIR program, Clos, Nickel, and Solórzano are presenting works they created during this 9-month residency wherein they are provided a stipend, are supported by DSH staff, and are charged with creating a 15-minute original work over which they have complete artistic control. They also meet as a cohort to discuss and present their work.

An eclectic trio of pieces resulted from the program this year, as different as the processes and guiding questions that produced them. But, as Clos observed, “We have a lot of similarities that I don’t think we would have been aware of going into the project, but through watching each other’s work and discussing it, we really are investigating things that have a lot of crossover.” She goes on to praise her fellow makers, “I respect them so much, and I’m grateful that I was involved in this particular cohort. They’re such intelligent, powerful, but humble people. It is such a pleasure to be around them.”

Solórzano agrees, “I like making alongside them, Adele and Ashley, in this cohort. They’re such intelligent, smart women.”

Nickel is also grateful for the “community we’ve built,” describing it as “one of the beautiful things that’s come out of this residency. I knew Ashley a little bit, but both she and Paty are thinking outside the box.”

As anyone who sees the three dances will know, the only box that could contain these particular artists would be as big as contemporary dance itself.

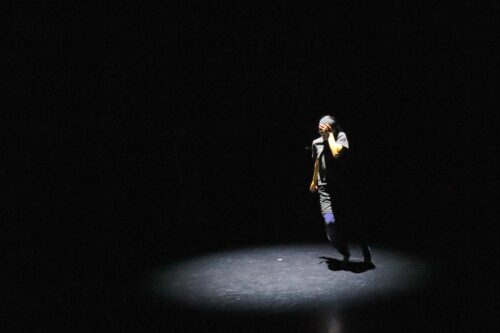

Star Power

Nickel’s subject is competition dance, and her approach is a sort of ethnographic and formal exploration of the genre, an exploration undertaken by Nickel and her collaborator, Brian Lawson. The two researchers and dancers met in graduate school at the University of Washington, unified by a love of classical ballet, a search for experience-forward dance pedagogy, and a drive to unpack form and content across dance genres and…forms. “There are all these different ways of talking about form, and playing with form,” Nickel explains. “We do that a lot in dance, but there’s less of a critical conversation of what that word means. That excites us as a next step.”

Nickel and Lawson’s “next step” is investigated on their shared website, formbelievers.com, an abstruse internet nook for semiotics and dance nerds. Check it out.

On the stage, Nickel and Lawson’s collaboration resulted in dances that are deliberately “advancing the form” of ballet by interrogating and “bending” some of its pillars, as in the dance Bow and Curtsy, presented at Mind the Gap in 2021, where the two performed a post-modern pas de deux, and Loose Ribbons, the 2024 ACDA South-Central gala performance cited by Catherine Cabeen as a queering of Jules Perrot’s Pas de Quatre. For Barnstorm, Nickel and Lawson move from the familiar territory of classical ballet to a form outside of their experience; the world of competition dance. In Texas, where school dance teams and competition studios train dancers in high-physicality, short-duration pieces for stage and stadium, the genre is ubiquitous. Not so in Nickel’s Portland, Oregon, dance origins, which better prepared her for balletic investigations. To confront the pillars of competition dance, to even determine what those pillars were, Nickel and Lawson interviewed competition dancers, many of them Nickel’s students at Sam Houston State University, where she is Assistant Professor of Dance. Lawson performed interviews from his location in Saratoga Springs, NY, where he is Assistant Professor in the Dance Department at Skidmore College. He described his approach as “lovingly challenging” the forms of competition dance after first “trying to understand it on its own terms.”

Nickel further describes approaching the new work, “Can we take what we’ve already played with and are interested in and apply some of those ideas to the competition dancer? We’re attempting to do this embedded in a population that knows a lot more about it than we do, but, at the same time, I think it’s a strength that as outsiders we see it differently.”

As for the “loving challenge,” Nickel clarifies, “One of the things that’s important is that we don’t want to spoof or dishonor it. It’s more that we want to peel back the exterior, to create some space between the form and our assumptions of its permanencies or its infallibility or its fixedness. Can form be flexible? Why not? It doesn’t mean we’re throwing the baby out with the bathwater. We can play with the form. Question it.”

As Nickel and Lawson developed their performative interrogation of form by choreographing for stage and film, as teachers they had to reckon with methods of transmitting the form that acknowledged its history, its power, and its possibilities. “We had this experience in our own training and working as dancers that was about sacrificing ourselves in service of this form,” Nickel describes, “and as we started to teach these codified forms, we found this collision in our value system. I love formal ballet training. But being inside of formal learning structures, I didn’t know how to also be myself. So, we’ve been talking about how to teach a ballet class where you honor the form but also give people a way to have their own experience inside of it. We’re looking pedagogically at teaching strategies for giving students opportunities for play inside of structure.”

The dancer-first pedagogy Nickel builds in collegiate classes informed her approach to working with Houston’s independent dance artists, some of whom were known to her at SHSC; dancers Aniya Wingate, Gage Self, Tuesday Moon Boswell, Caitlyn Cork, and Olivia Salazar make up the

cast of Star Power. “Most of this show originated in the dancers’ bodies and then has been crafted and edited. I pivoted early on in my process to drawing material together with the people in the room. Working like that has been much more successful and more interesting for me, and it aligns with my values in terms of the experiential component. I want to treat the dancers I’m working with as intelligent, layered, complex human beings with lots to offer the process. It’s more efficient, it makes more sense, and it helps the dancers feel more invested in the work because they’re getting to be themselves or feel they are contributing some genuine part of themselves to the process.”

Ghost

Ashley Clos also spent recent years in the collegiate world of dance, teaching at San Jacinto College, Lone Star College, and Clos’ alma mater, Sam Houston State College. The dances she choreographed for students often advanced to national festival performances, but it is the AIR program that provided an opportunity to work exclusively with independent Houstonian artists. This is one of the three significant departures Ghost has taken from Clos’ accustomed mode of dance-making. First, the residency gave her the chance to employ not only independent dance artists but artists outside of dance as collaborators. Second, working closely with Houston indie music luminary Brett W Taylor meant that the score to Ghost developed ahead of the choreography. Finally, Clos has inhabited Ghost with a fantastical sense of drama, ungrounded from real life yet teeming with resonant emotion, unlike previous work that asked dancers to draw from real-life responses. Like previous work, this one takes place in a world made from both intuition and artistic specificity, carefully tended by the choreographer.

“I love creating worlds,” says Clos. “Building something all-encompassing and controlling every moving part is so exciting to me. I think that what I bring to dance is not just movement-based or research-based, but it’s always to do with transportation of the audience.”

It is her idiosyncratic, discovery upon discovery, surprising-but-not-accidental method of research that allows the worlds to be so texturally rich, to be transportive and compelling. In a word, the method can be described as synchronicity, a concept that cannot be pinned to actions more solid than experience widely and stay aware. Clos is adept at both.

“I find that it’s difficult to explain the path because it is so personal and it feels like lightning is striking, but I trust it. I don’t want to over-investigate it. It works for me,” she explains.

A lightning strike for this project was identifying the fact of synchronicity in her own process. Clos read Carl Jung on the archetype called the ‘ghostly lover,’ a trope common in the romantic era dramas to which Ghost refers. In investigating this archetype, Clos found that “Jung talks about paying attention to synchronicities in your life that will guide you to the right path, or be an assurance that you are on a path. Creatively, that makes a lot of sense to me. It is something I have been living for many, many years, but I didn’t know how to identify it. Exploring Jung was like an awakening to my own creative practice.”

While synchronicity is powerful in the research phase of her choreography, Clos’ work in the studio is based on intuition. “The cerebral experience of all the research and the excitement and the inspiration feels separate in a way from what happens in the studio,” she explains. “The way it actually feels in the dancing body, the way it comes out in the choreography, it has a different life than that first step.”

Structurally, Ghost is an homage to Giselle, “the quintessential romantic era ballet” according to Clos. “I remember being enamored with the mad scene as a young girl, which is funny, but it was something that wasn’t explored in ballets I was used to seeing. Here, I’m investigating personal matters, and ballet training, but mainly paying some kind of homage to a ballet that I care about aesthetically.”

“I don’t want anyone to think they need to know the premise of Giselle to appreciate or understand my work,” Clos emphatically reassures. “That’s very important to me. If I’ve done a strong enough job and a clear enough job, then it will speak for itself. And it will intentionally be my rendering.”

Clos’ collaborators are dancers Isabella Vik, Timothy Amirault, Courtney S. Allen, Tuesday Moon Boswell, Lindsay Cortner, Lillian Glasscock, Aniya Wingate, and Zoe Vela. Friend and jewelry artist

Rachel Duane contributed to costuming, and the music, as mentioned, was composed by Taylor. Clos describes the work as “merging the Houston craft and music and dance worlds in a way that we need more of. We need more cross collaboration. It creates a different texture, and I’ve been relying on these artists. I tend to be a do-it-all kind of director. I think we are all like that in dance, very DIY, but, it is a luxury to have people you can call on who are experts in their field. You say, ‘This is what I’m thinking,’ and they provide you with art that is so fantastic, better than you could imagine, and that’s what I’m experiencing with Brett and Rachel.”

Because her work with Taylor resulted in a music-first dance-making process, his “sonic landscape” is fundamental to the world, and the drama, of Ghost. For example, Taylor used bells, cymbals, and strained vocal loops in what he described as the “strange, frantic, climactic” score of a scene of total cognitive destruction, the mad scene, a chaotic solo danced by Vik. “There are notes that shouldn’t be there,” said Taylor, while Clos pointed out the “little bit of levity” that pop song references brought to the piece. The pop songs were suggestions from Clos, and it is this hand-in-hand, back-and-forth style of collaboration that let Clos relinquish areas of creative control while ensuring she had what she needed to build her piece, to build the world she intuited.

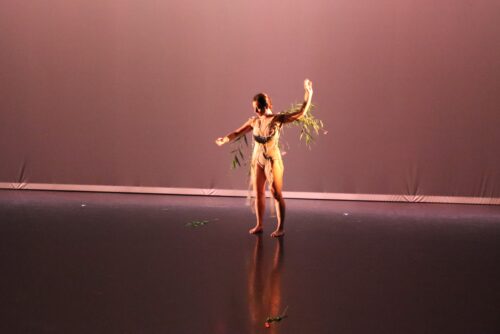

La Maleza

Paty Lorena Solórzano considers herself a transplant, searching for ground to nourish her roots. Born in Mexico, Solórzano graduated from high school in the Houston area, did her BFA in dance and photography at Texas Christian University, moved to Michigan for her MFA, taught as Professor of Dance at Universidad de las Américas Puebla in Mexico, and returned to Houston to be closer to family, returning to a community she knew through past work with Hope Stone and Psophonia, among other Houston dance exemplars. Like the other AIRs, Solórzano trained and performed around the country and the world. Her work with Jennifer Monsen and Jill Sigman particularly informed her work on La Maleza.

“A friend said she feels like all my work is truly about migration. Maybe I just keep making the same thing, in a different way.”

Her 2024 piece “Memoria entre alas” for Danzas Migratorias: Coreografía de la Mariposa Monarca certainly fits that hypothesis. To make the dance, Solórzano studied monarch butterflies, whose migratory lifespan takes them across North and Central America. “I wanted to really get to know the butterflies, to observe them like a scientist. But, not just as a scientist studying a species, rather asking ‘What are you trying to tell me? How can I be part of this conversation with you?’ When I went into the studio, this specific movement language emerged out of what I had observed.”

Solórzano has taken this deep, questioning process to other areas of work, including, for her Barnstorm piece, the study of weeds, or las malezas en español. Weeds, it is important to acknowledge, are just trying to thrive and reproduce like any other species. They are indifferent to their designations as native or non-native, invasive or noninvasive, noxious or not noxious; these are not their concerns, though the labels do inform how people decide where plants can and cannot be allowed to live.

“In this project, I was curious about plants and the idea of the weed as a metaphor, and the metaphor of trying to find roots in maybe an inhospitable place. I’m tying it very abstractly to my feelings that I’ve had of not quite belonging anywhere. I am an immigrant here and when I am in Mexico, I am different by my growing up here. I’m curious about that and I’m curious about the intelligence of plants and how they communicate, what they are trying to tell us. I’m linking this through a personal connection, and also political, and very biological processes. When I research, I dive deep and try to read as much as I can about everything, but it’s not until I go in the studio that I say, ‘How am I going to put this in my body in a process?’ And I ask a question, very concretely, then I set like a 15-minute timer to record my movement and say, ‘Let’s figure it out in the body in a 15-minute improvisation.’ Then I look back at the movement and I see, ‘Oh, this was interesting, this gesture, where did it come from?’ I’m sure it is informed by everything else I have been doing. So that is interesting to me, how things emerge out of an ‘intellectual’ process into a more bodily process, which is also intellectual, too.”

The bodily process is intellectual in that Solórzano – like other movement artists – does not distinguish between the life of the body and the life of the mind, between intellectual knowledge and embodied knowledge. “A huge part of my process is thinking through the body, through improvisation, as a way of asking questions in real time. I understand things more clearly through movement, and then I can put them in words, but it is informed by what I do with my movement and what I observe in the movement. I don’t think they can be separated. They are the same thing.”

The world of nature and of politics also cannot be separated. Solórzano discusses the need for workshops, for more ways she can share her realizations “to help us work through this relationship. We can connect and understand how everything is related. I cannot unrelate what I’m doing from what is happening in this country right now. I think about the quiet rebellion of weeds. I do believe we need some more radical changes, but there is power in the quiet rebellion, too.

“Another thing I’ve been thinking a lot about with this piece is this lost reverence or devotion or relationship to other plants and what’s around us. You’re the same as me, I am the same as you, even to the smallest clover. Which I think is quite healing.”

La Maleza is performed to music by Anthony Almendárez with costuming and concept collaboration by Nicole Sara Simpkins and dramaturgy by Efrén Cruz Cortés. La Maleza is performed as a solo, but, because everything is connected, “I don’t believe solos exist,” explains Solórzano. “I truly don’t. I think it’s always in relationship with something, with someone.”

Recent Comments