Art as Empathy, History Lesson with CORE

Photo by Lynn Lane

On January 27, the President of the United States signed Executive Order 13769, officially titled Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States. The order halted the U.S. Refugee Program for 120 days, suspended the entry of Syrian nationals, and temporarily barred entry to citizens of seven Muslim-majority nations.

The decree came just one month shy of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the signing of Executive Order 9066 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, which resulted in the relocation and internment of nearly 120,000 Japanese Americans during World War II. The national fear of the time was that these citizens of Japanese descent would be loyal to the imperial motherland, although a great percentage had been born on American soil.

Photo by Lynn Lane

Life may imitate art, but can the living learn from it? Executive Order 13769 suggests not, but perhaps there is a glimmer of hope. Sue Schroeder of CORE Performance Company believes so.

On February 17 and 18, the company remounts its Life Interrupted, an examination of the Japanese American internment experience, at Asia Society Texas Center. For Schroeder, the current national bent towards xenophobia makes the work all the more relevant. “There is a lack of empathy, and a lack of developing that empathy,” she observes. “This order is a limitation to another perspective. We can get to know people and realize that, yes, we’re different, but we’re all human beings.”

Schroeder cites her experience with bringing in the artists for her October Miller Outdoor Theatre engagement of CORE Presents Dance from Israel. “The VISA process was grueling,” she says. “They were denied once, and the whole episode showed me that there’s this huge disinterest in learning about people from other cultures. It’s there because we’re breeding it.”

Life Interrupted premiered in the fall of 2015 and was born out of CORE’s longtime partnership with the University of Arkansas. Dr. Gayle Seymour, an art historian and director of the university’s artist-in-residence program had long been interested in how the company worked with movement and visual art exhibitions. Arkansas is home to the two most eastern internment camps, and to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the closing of the camps, Dr. Seymour asked them to create a work.

To handle the weighty material, Schroeder dived headfirst into research; Life Interrupted marked the first time she hired a dramaturge for a project. “There was a lot of research involved, and a lot of anecdotal stories,” she explains. “We needed to know the history.” Movement was developed simultaneously. About eight months before the premiere, the company was commissioned by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston to create work for two exhibitions, one of Japanese screens and the other of Japanese post-war photography. “We tried to find the commonality between the two projects, and understanding what the Japanese aesthetics are.”

To handle the weighty material, Schroeder dived headfirst into research; Life Interrupted marked the first time she hired a dramaturge for a project. “There was a lot of research involved, and a lot of anecdotal stories,” she explains. “We needed to know the history.” Movement was developed simultaneously. About eight months before the premiere, the company was commissioned by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston to create work for two exhibitions, one of Japanese screens and the other of Japanese post-war photography. “We tried to find the commonality between the two projects, and understanding what the Japanese aesthetics are.”

Leslie Scates worked with the company on ensemble movement, and Celeste Miller, who layers movement with stories and text, also shaped the practice CORE’s artists drew from.

During the research phase, Schroeder learned much about this low-point in American history. “For starters, I was surprised about how many people don’t know that this happened,” she says. And if few people know about the internment, even fewer still know about the paradoxes that defined daily life in the camps.

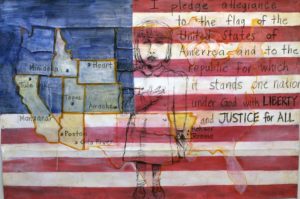

“Children were required to say the pledge of allegiance every day, and several years into the experience, the U.S. military ran out of troops, and so started recruiting within the camps. There were Japanese Americans who served even while their parents were imprisoned.” The 422nd Infantry Regiment, almost entirely made up of Americans of Japanese descent, in fact, proved to be the most decorated unit of size in American history. “They were fighting to prove their loyalty to this country,” says Schroeder.

Photo by Lynn Lane

The design of Life Interrupted, like its material, also comes from life in the camps. Scott Silvey’s scenic design is constrained to only the items that were issued to prisoners on arrival: a mattress for each person, a stove, and a single light bulb. Crates were used for everything else, including makeshift furniture. Visual art is by Drury Professor of Architecture Nancy Chikaraishi, whose work Schroeder first saw at the World War II Japanese American Internment Museum. “I saw Nancy’s work and immediately wanted her involved.”

Even though Schroeder says she was proud of the 2015 premiere, she is excited about the remounting of Life Interrupted. The cast has been expanded to eight, and the material feels even weightier, more urgent. “We had a small group in last week to see this version, and most people in the room were weeping,” she says. “My hope is that this starts a conversation. The company feels there’s no time to waste, that this work has to be done. We have to do it, and we’re using it to get through these times.”

Adam Castaneda is a dancer, writer, and arts administrator in Houston. He is the Executive/Artistic Director of FrenetiCore, and performs with Suchu Dance, the Pilot Dance Project, Bones and Memory Dance, and Holding Space Dance Collective.

Recent Comments