Kyle Abraham Goes Untitled in Exploration of Black Love

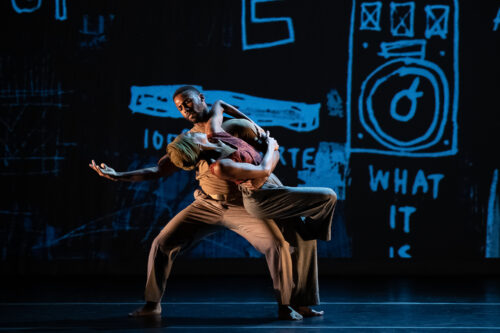

Photo by Christopher Duggan

Listening to the music of D’Angelo is a kind of sensual, indulgent experience that is rooted in the pleasure of being in one’s own body. The crooner’s voice is rich in texture, and sultry in pitch, fully realizing the seductiveness of masculinity while recognizing its potential for softness and comfort.

D’Angelo’s music is also a throwback to a specific time in pop culture, when not only R&B acts, but their sound, was being pushed to the forefront of the mainstream music industry. I was a freshman at a Black high school when D’Angelo’s iconic Untitled (How Does It Feel) was in constant rotation on MTV and VHI, and the neo-soul movement was in full swing. Erykah Badu, Maxwell, Angie Stone, Jill Scott, and, of course, D’Angelo, were what my classmates and I were listening to during an era when the glittery, highly produced music of the late 90s was giving way to something a little more real.

This cultural specificity is where choreographer Kyle Abraham places his most recent evening-length work, An Untitled Love (2021), which passed through Houston on the evening of May 6 at the Wortham Center’s Cullen Theater, courtesy of Performing Arts Houston. Set to D’Angelo’s catalogue, An Untitled Love explores Black love in all of its forms, from the heterosexual to the unapologetically queer.

What struck me most about the whole production is that Abraham managed to do what is so hard to do in contemporary dance. He created a vibe, an ebb and flow that was more mood than artifact. It began the moment we walked into the Cullen Theater with a pre-show playlist that conjured the possibilities of an informal house party, and was maintained throughout the duration of the work by Dan Scully’s striking scenic and lighting design.

Scully’s set offered context in abundance despite its minimalism. A sofa, a rug, and a lamp set the scene for Abraham’s soulful social, which was filled with flirtation, coquetry, and bravado-fueled courtship. Two light strips, at times a searing red and at others a doleful purple, marked the downstage parameter and cut across the background art, creating a familiar accent of urban living. When young people gather for a party, the light strips come out for a bit of nightclub flash. The visual cue is clear: the people who inhabit this work are freshly minted adults who can still manifest joy from a good house party and a dance or two.

The visual aesthetic holds Abraham’s movement well. It’s luscious and warm and earthbound, much like the vibrant earth tones the dancers are costumed in. Each dance step moves effortlessly into the next, with Abraham’s contemporary style intermingling with a more groovy, every-person sensibility. The dancing is beautiful, and it’s a manner that is less focused on static shapes than fully embodying the movement through the spine.

When the dance really gets moving, it’s captivating. But the problem is that Abraham is attempting to recreate a kickback, a low-maintenance gathering of friends with none of the frills of an all-out party. To really enjoy a kickback, you have to be a participant. To know the players, you have to be one of them. I loved being in this mood, but I didn’t want to watch it, so much as be a part of it. It’s a difficult task to keep this ebb and flow engaging on a choreographic level. The dancers meander on and off stage, just like when people come in and out of an informal house party, but after the first twenty minutes, the anemic transitions start to weaken the effect as a whole. It’s unfortunate, because there are some really inspired moments that should be supported by weightier movement.

There’s a really fun scene in which dancers filter onto the stage in slow motion, the action of the party distilled down to its finer details of gesture, facial expressions, and greeting ceremonies. And there’s a sequence that sees four of the women on the couch engaged in gossip and womanly affectations. The dance is seated and is expressed through lovely hand sequences, shoulder articulations, and positions of the head. I remember vividly a joyful solo by a woman dancer whose character is in the throes of an early romance; her movement is composed of big, expansive sequences that open her heart chakra to her paramour, to the world, and to us, the audience.

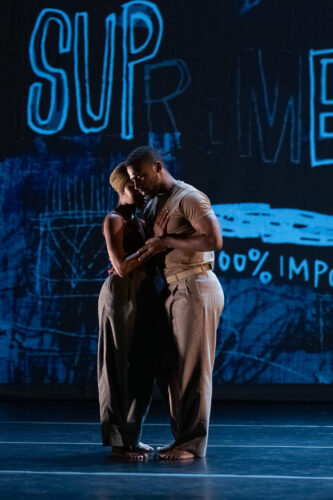

Photo by Christopher Duggan

Of course, it’s no surprise that the highlight came from the impressive male solo danced to D’Angelo’s iconic Untitled (How Does It Feel), performed with so much passion it was palpable beyond the front orchestra seating. The solo came after a brief reminder of the social injustice that remains prevalent in contemporary America, a moment that takes the viewer out of the intimate space we had been visiting.

For me, this was a grave reality check, that the nuance and complexity of Black love is complicated further by this layer of ominousness. Love must face the tests of the world, but this particular love must also withstand the brutality of an inhospitable landscape. The Untitled soloist not only embodies the frustration of a tumultuous romance, but the anger that can only be harnessed from knowing that he is an object of hate.

An Untitled Love ended with some comedic antics and a joyful sense that despite the gravity of the penultimate scene, life and love go on. Though a bit laborious in its quieter moments, the work is big, bold, and everything beautiful.

Recent Comments